Widow's War

Illustrated Tour of Lyddie Berry's Satucket

See Photo Gallery Below

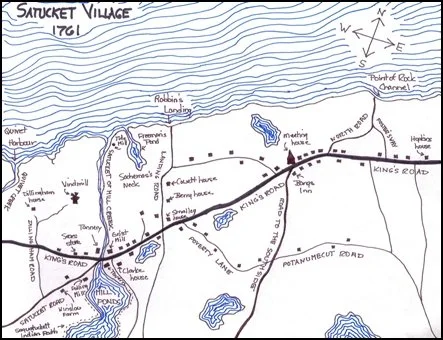

Lyddie Berry's Satucket Village is today's Brewster, Massachusetts, located inside the elbow of Cape Cod. As you take this tour picture the roads not as tar but as a mix of sand, mud, and ruts. Imagine that you are on foot or horseback. If you're a woman you would likely be perched sidesaddle on a small pad called a pillion strapped behind the man's saddle, clutching at a belt provided for that purpose. The horse would have to be kept to a modest pace to keep you on board, and so you should travel now, in order to spot the old houses and ancient stone walls that line your way.

The eighteenth century "Cape Cod house," an architectural classic which can be seen now in many parts of the country, began here, and one winter spent on Cape Cod might tell you why The houses were built on low foundations close to the ground with short walls and steeply pitched roofs to fend of the fierce Cape Cod wind, constructed around a large central chimney exiting through the ridgeline, the central location of these chimneys serving to keep the heat where it was needed and provide fireplaces on all sides. The typical Cape Cod house included a "half story," or unfinished attic, where the children slept as the family grew, the only light in this dormer-less space coming from often odd-sized and placed windows in the gable ends. The front-facing windows were small-paned and tucked up tight under the eaves; the door might be topped by "lights," or a row of small, square panes of glass. A "full Cape" will have four windows, two windows on each side of the central door; a "half Cape"will have two windows to one side; a "three-quarter"Cape will have two on one and one on the other. A half Cape or three-quarter Cape might be added on to become a full Cape, but conversely, cantankerous relatives have been known to split a full Cape in two. Inside, the full Cape was divided into two front rooms, one usually a parlor and one a bedroom, and a long "keeping room" or kitchen/living space behind, this long room flanked by a buttery (named after "butts," or large containers for wine, being the room where provisions were stored) and at least one tiny bedroom, the one nearest the fire's warmth being the "borning room," or sick room. Even the half house would manage to fit in a small front parlor and bedroom as well as keeping room, buttery and borning room behind. A round "Cape Cod cellar" would be reachable through the buttery floor.

The "salt box," another popular architectural form of the day, got its name from its resemblance to early containers for salt. The salt box might rise a full two stories in front, but the rear roof-line would drop almost to the ground. As the houses usually faced south, this roof-line added additional protection against the north wind. The interior first floor of a salt box would not differ greatly from a Cape Cod house, but the second floor would be divided into finished bedrooms, or chambers.

As time went on and a more affluent class developed, a Georgian style of architecture appeared, with larger symmetrical houses of two full stories, but still boasting a central chimney through the ridgeline and small-paned windows with simple trim. The lights above the door might be semi-circular or made of small square panes of glass as before.

To follow in Lyddie's footsteps, enter Brewster from route 6 via route 124 at exit 10, and continue past the ponds to take a left on Tubman Road (Lyddie's "Poverty Lane"). Poverty Lane will intersect with Route 6A or Main Street (Lyddie's "King's road"). Turn left on Main Street and continue until you come to a fork in the road. Take a left at the fork. This is Stony Brook Road; today's Main Street forks to the right here, but in 1761 that part of Main Street didn't exist -- rather it continued left toward one of the two main structures in town: the grist mill. Note the lovely example of a half Cape, circa 1750, minus the addition behind, two tenths of a mile along this road on the right. Continue along Stony Brook until you come to Old Run Hill Road. Nathan Clarke's house sat on this rise overlooking the mill, although the original ancient house on this site has since been replaced. Here Lyddie Berry lived with her son-in-law after her husband drowned. Continuing along Stony Brook Road you will pass a large, white Georgian style house on the left; this is the tavern (see photo gallery below) where Eben Freeman stayed. A nineteenth century version of the original grist mill sits just beyond on the site of the eighteenth century fulling mill (the "fulling" process tightened the weave in homespun cloth) which burned down in the middle of the Winslow-Clarke feud. In Lyddie's day the grist mill sat diagonally across the road to the right of the brook, with the tannery where Silas Clarke worked on the opposite side. This brook, today called Stony Brook, was variously known in Lyddie's day as the Satucket river, the mill stream, or the herring river.

Park in the parking area on the right of Stony Brook road just beyond the brook and take some time to walk around on both sides of the road. Picture this a busy center with one mill grinding corn, another fulling cloth, and the tannery processing leather; picture the tavern comings and goings, and the herring men catching, salting, and packing their fish into barrels to be shipped to the West Indies to feed the slaves. Today the taking of herring is prohibited, but if you visit in late April or May you might still catch the fish leaping the stone ladders and struggling upstream toward the mill pond to spawn. Before the colonists came the Sauquatuckett Indians set up their winter encampment between the upper and lower ponds; the herring's return each spring signaled their own move to a summer camp nearer the shore. In Lyddie Berry's day a small remnant of the old tribe still lived in their tradition wetus beyond the mill pond. If you visit the mill in the summer season you may watch the miller grind corn and then stop in at the museum upstairs where you might find a weaver at work on a loom similar to one Lyddie might have used.

Continue your tour along Stony Brook Road and follow its right fork beyond the mill. (The left-hand fork is still called Satucket Road, and on its immediate left you might glimpse the 1738 Nathaniel Winslow house, once a sizeable farm, and Lyddie's main cheese competitor.) Continue along the right fork of Stony Brook -- Lyddie walked this route to Sears's store. Take a right on A.P. Newcomb Road; you will meet up with route 6A and find yourself facing the oldest house in Brewster and likely on Cape Cod, parts of which date back to the seventeenth century. This is the Dillingham house , a salt box, home of Nathan Clarke's so-called "damned Quaker." If you turned either left right on this part of 6A you would be traveling along a road that didn't exist in Lyddie's day, although there are old houses on this road that were reached from the King's road via narrow cart ways. Take a right here and you will come to Drummer Boy Park, worth a stop in season to visit the restored eighteenth century windmill and small one-room house on the grounds. If not in season, the park still affords a fine view of the salt marsh and Cape Cod Bay beyond. In Lyddie's day this marshland was valuable not for its water view but for the salt hay, which fed their cattle.

Returning to 6A you will pass the Cape Cod Museum of Natural History, also worth a stop, as a stunning nature trail out to Wing's Island will take you to one of the Saquatuckett Indians' summer encampments, and later the property of one of Satucket's first English settlers, another Quaker named John Wing.

Continuing along 6A you will cross over Stony Brook to your right, or Paine's Creek to your left -- the river changes its name as it crosses 6A. About a half mile from the museum, again on your left, you will find a good example of a three-quarter Cape house. Two tenths of a mile beyond you will turn left onto Brier Lane, or Lyddie's "landing road." She and Sam Cowett lived in Cape Cod houses along the right side of this road, and here is your ultimate test: see if you can spot two old Cape Cod houses on the right, buried under layers of additions and dormers. Hint: the original houses would have faced south, at right angles to the road. Lyddie walked from here through the woods to the river to do her fishing out of sight of the herring men.

Continue along Brier Lane until it intersects with Lower Road. Turn right and then quickly left onto Robbin's Hill Road. (In 1761 this road connected to Brier Lane to form one long "landing road," running from the King's road to the bay.) This road will take you to one of Brewster's seven town beaches, now called Saint's Landing, but this was Robbins's landing in Lyddie's day, and this little dip in the shoreline was one of the town's two main "ports." From ancient times through modern day pods of whales have stranded along this shore; here Lyddie came to look for Edward's boat, and again to look for his body, when she observed the butchering of the whales and the trying out of the oil. Later she returned to harvest clams off the sand flats that stretch far into the bay at low tide, but if you venture onto the flats keep a careful eye on the incoming tide; Lyddie's near-drowning experience is as common today as it was then.

Return to Lower Road and take a left, then another left on Main Street, following the route Lyddie walked to church. Just before the church you will pass the town "egg," or town common in Lyddie's day, were the local militia drilled. The church ahead is not the original 1700 church but an 1834 version; the cemetery in back of the church, however, is the original burial ground, holding graves dating back to 1703 which bear the names of many Freemans, Berrys, Hopkinses, and Clarkes. This is where Lyddie watched the burials of her children, her husband, and Rebecca Cowett, a Christian Indian. Eighteenth century church services lasted several hours in the morning and again in the afternoon; the building across the street from the church sits on the site of the original Bangs Inn, where Lyddie and the Clarke family passed time between services.

Continue left along Main Street. The Edward Snow house, a short distance beyond the church on the right, was built in 1700 (minus the modern addition in back). Note the mismatched windows, indicating that this house might once have been a half house, later turned into a full Cape. The Edward Snow house was the model used for Lyddie Berry's home; you will get a better view of this house on your return.

Continue about a mile along Main Street and you will see another full Cape on the left, with an eighteenth century barn at the back; the barn is datable by the door in the long side of the structure instead of in the gable end. Another half mile along Main Street you will come to the Hopkins House. This property was originally owned by the grandson of Stephen Hopkins of the Mayflower -- it is believed the original part of this house was built by an eighteenth century member of that family -- and this is where Shubael and Betsey Hopkins lived. Turn around at the Hopkins House and follow the beginning of Lyddie's route as she walked from Cousin Betsey's to her old home by taking a right at Foster Road and staying straight all the way to the water. This is the Point of Rocks landing, the second major "port" of Lyddie's day; Lyddie walked westward along this shore all the way back to Robbin's Landing and her old home. From here you can see the curve of Cape Cod's "arm" and the towns "down Cape" from Brewster -- today Orleans, Eastham, Wellfleet, Truro and Provincetown (out of sight except for it's needle-like monument, visible on a clear day), but in 1761 Orleans was still part of Eastham, Wellfleet was called Billingsgate, and Provincetown was often referred to simply as "Cape Cod," the name of its harbor. You will reverse direction here and take the right fork onto Point of Rocks Road. Continue along Point of Rocks Road, past the cranberry bog to the next tarred intersection, and turn right. (The road straight ahead did not exist in 1761, although on its left you will find a beautiful example of a 1745 Cape half house that was later moved to its present location from Billingsgate Island, the "Cape Cod Atlantis," which disappeared into the bay off Wellfleet in the 1940's.) The road you are now traveling is called Old North Road, but of course in Lyddie's day it was simply "the north road," leading from the King's road down to the bay.

From here you may return the way you came by taking a right on Main Street and then a left on route 124 back to the route 6 highway, or you may continue along route 6A to the mainland. This road has been straightened and widened in spots, and of course tarred, but it is still essentially the slow and winding "King's road" of Lyddie's day. You will pass through Dennis and Yarmouth before entering Barnstable; in 1761 Dennis was still part of Yarmouth, but often called Nobscusset after its Indian tribe or Sesuit after its harbor; you will pass many eighteenth century houses along the way. In Barnstable, not far beyond the traffic light, look to your left at the courthouse; the statues honor Barnstable natives James Otis and Mercy Otis Warren. About a mile farther down the road on your left you will spy Crocker Tavern, the sole survivor of a row of early taverns grouped around the original courthouse, which sat on the south corner of route 6A and Pine Lane. You are now in Eben Freeman's neighborhood. A little over half a mile farther along, turn right down Scudder Lane (Calf's Pasture Lane in 1761). This road will end at Barnstable Harbor, where Shubael and Lyddie landed in the sloop Betsey; if the tide is right, you might see the shoal where they ran aground on their return trip to Satucket.

Reverse direction and continue along route 6A until you come to the intersection with route 132. Check your odometer; exactly one and a half miles from this intersection you will be in West Barnstable ("Great Marshes"in Lyddie's day); look to your right and you might spy a plaque that marks the site of the original Otis homestead, long since destroyed. Lyddie Berry never made it inside the Otis's elegant home on her 1761 journey to Barnstable, but she has the advantage over today's traveler -- she might just make it there next time.

Double click on an image below to open a slideshow gallery

Widow's War - Read an Excerpt

Widow's War - The Story Behind the Story

Widow's War - Reading Guide

Widow's War - An Excerpt From Thomas Clarke's Last Will and Testament